From the 16th century on, the six nations have allied themselves to form the Iroquois Confederacy. They call themselves Haudenosaunee, the People of the Longhouse. The Mohawk nation has historically stood guard at the easternmost door of a symbolic longhouse in New York State. The Seneca nation watches over the western door, while the other nations - the Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and the Tuscarora (joined in 1722-23) - are spread in between.

Skilled in warfare and gifted in peace, the six nations established a peace treaty that led to the formation of one of the world's earliest democracies. This society gave rise to great orators, like the Onondaga's Hiawatha; and noble leaders, such as the Seneca war chief and leader, Cornplanter, who was rewarded with a tract of land along Pennsylvania's Allegheny River for his diplomatic efforts with the fledgling government of the American Colonies.

Elm Bark Trays

(Left) George Key, Canada, Wolf clan, Seneca, pre-1910

(Right) Seneca, pre-1910

In the spring and early summer, when the sap was up, bark was peeled from elm trees and bent to make trays and bowls. These items served every conceivable culinary purpose. They held cooking ingredients and prepared foods, and made good mixing bowls and dishpans. On occasion, Iroquois women even added hot stones to bring the liquid in larger bowls to a boil, or they carefully placed the vessels over the fire to heat water.

The Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois Confederacy was a sophisticated political and social system. It united the territories of the five nations in a symbolic longhouse that stretched across the present-day state of New York.

The original five nations of the Confederacy were divided into two groups: the Elders, consisting of the Mohawk, the Onondaga, and the Seneca; and the Younger, consisting of the Oneida and the Cayuga. Despite this distinction, all decisions of the Confederacy had to be unanimous.

The decision-making process mirrored the creation of peace among the Iroquois Confederacy. The Onondaga nation introduced a topic and offered it to the Mohawk nation for consideration. When a decision was reached, they passed it to the Seneca nation. A joint decision was announced to the groups across the fire for deliberation. When these groups reached an agreement, they reported to the Onondaga Council Leader. If he agreed, the decision was unanimous. If not, the negotiation process began again with the Mohawk nation. If unanimity were impossible, the matter was set aside and the fire covered with ashes.

At the conclusion of a session, the acts of the council were recorded in the belts of wampum that chronicle events of significance.

To this day, Iroquois law remains unchanged. It continues to guide the Grand Council of the People of the Longhouse and has influenced nations outside of the Confederacy as well. The structure of the Iroquois Confederacy likely inspired the American colonists' development of the U.S. government.

Pipe Tomahawk

Northeastern United States, ca. 1811

Unidentified wood, pewter, brass; L 51.0 x W 2.5 x H 16.5 cm; 23102-1199, gift of John A. Beck

The pipe tomahawk is an ingenious combination of weapon and smoking pipe, developed by Euro-Americans for trade with Native people. Iroquois men traded furs for these popular tomahawks. Ornate examples were presented at treaty signings as diplomatic gifts to Indian leaders, who carried them as a sign of their prestige.

The Great Peace

Before the arrival of the Europeans, an unending series of wars and feuds among the Iroquois nations nearly destroyed their civilization.

A visionary Huron named Deganawida appeared in Iroquois territory with a message of peace—13 laws that promoted peace without violence. An Onondaga man named Hiawatha became a strong supporter of the "Peace Maker."

Hiawatha, a great orator, traveled to the other nations and submitted the plan for their consent. A Mohawk woman was the first person to approve the plan. Her actions symbolized the importance of women to the Iroquois political process. The Iroquois chiefs subsequently approved the plan.

Only the Onondaga chief Thadodaho stood in opposition. Hiawatha explained his vision and finally won Thadodaho's approval--with one concession. Thadodaho said he would join only if he would be considered "first among equals." To show respect for the reluctant chief, meetings of the Iroquois Confederacy were always held in the principal Onondaga village, and the Onondaga chief served as the Council Leader.

Wampum

Since they had no writing system, the Iroquois depended upon the spoken word to pass down their history, traditions and rituals. As an aid to memory, the Iroquois used shells and shell beads. The Europeans called the beads wampum, from wampumpeag, a word used by Indians in the area who spoke Algonquin languages.

The purple and white beads, cut from the shell of the quahog clam, ground and polished and then bored through the center with a small hand drill, were arranged on belts in designs representing events of significance.

Certain elders were designated to memorize the various events and treaty articles represented on the belts. These men could "read" the belts and reproduce their contents with great accuracy. The belts were stored at Onondaga, the capital of the confederacy, in the care of a designated wampum keeper.

Image: George Washington Covenant Belt (Reproduction)

Jake Thomas, Cayuga, Six Nations Reserve, Ontario, 1995 -1996

Plastic (electrical wire insulation), nylon artificial sinew, Rit brand commercial dye; 36329-1

The original Washington wampum belt is most often identified with the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794, which pledged peace between the United States and the Six Nations of the Iroquois. However, it was probably a gift to the Iroquois Confederacy from the United States at a treaty signing in 1789.

This is a reproduction of the original belt, which is constructed of white and deep purple shell beads made from the quahog clam (Mercenaria mercenaria). The original belt stays in the custody of the Onondaga Nation, the keepers of the League central fire.

Cornplanter

During the American Revolution, the Iroquois warrior Cornplanter rose to prominence, becoming a principal Seneca leader. He was also known as John O'Bail after his Dutch trader father.

After the Revolution, Cornplanter quickly decided that keeping the peace with the new Americans was the best way to help his own people. Although his mission as a peacekeeper was often unpopular and difficult, he negotiated the best possible terms for his people on numerous occasions when he traveled as a statesman to Philadelphia.

In gratitude for his assistance in keeping the Seneca neutral during the Indian wars in Ohio, Cornplanter was given a grant of land. In 1791, the grateful Commonwealth of Pennsylvania established Cornplanter's Grant along the western bank of the Allegheny River.

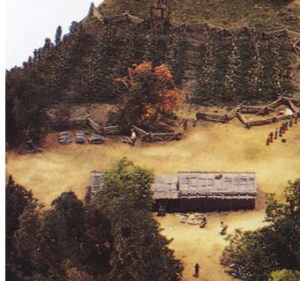

Cornplanter's Grant

Cornplanter's Grant was not really a reservation, since the land was a gift to Cornplanter as an individual. Because of its geographic location, wedged between the banks of the river and the mountains, the grant offered a measure of asylum and insulation from the pressures of a new expanding nation. Here the Seneca people could continue to plant, hunt, and live their traditional lives.

In 1798, 400 Seneca (one-fourth of the total Seneca population) lived on Cornplanter's Grant at the town of Burnt House, or Jenuchshadego. Many were major figures in the Iroquois Confederacy. Noted residents included Cornplanter's half brother, the prophet Handsome Lake; his uncle Guyasuta; his nephew "Governor" Blacksnake; and Blacksnake's sister, the leading woman of the community and clan mother of the Wolf clan. Cornplanter believed it would be advantageous for the Senecas to receive education in English and other Euro-American skills, so he invited the Quakers to come and teach at Cornplanter's Grant.

Kinzua Dam: A Broken Promise

Though given to Cornplanter in perpetuity, Cornplanter's Grant was confiscated by the U.S. government in 1964 by order of eminent domain to construct the Kinzua Dam.

In 1965 the United States Army Corps of Engineers completed Kinzua Dam. Its rising water inundated all of the habitable land of Cornplanter's Grant along with 10,000 acres of the Seneca's Allegany Reservation in New York.

Cornplanter's descendants and the Allegany Seneca fought to halt the construction of the dam. They cited the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794, the oldest active treaty in the United States. This agreement, signed by both George Washington's representative and Cornplanter, guaranteed that the United States would never take the Seneca's land. This agreement states:

Now the United States acknowledges all the land within the aforementioned boundaries, to be the property of the Seneca Nation, and the United States will never claim the same, nor disturb the Seneca Nation.

As Seneca G. Peter Jemison pointed out in 1998: We known that that treaty is still being recognized because every year in the fall … we are sent treaty cloth…. Our clan mothers say, “We don’t care if it [the cloth] gets down to the size of a postage stamp; the principle is that you are still giving us that cloth because you recognize that this treaty is still in place.”

Handsome Lake

While Cornplanter's half brother Handsome Lake, lived at Cornplanter's Grant, he founded a new religion. It emphasized a revitalization of the traditional seasonal ceremonies, a strengthening of the family, and a prohibition against liquor. Handsome Lake's teachings were based on a series of visions. Dreams were an important instrument for revelation, and visions were received as divine prophecies.

In 1799, Handsome Lake had the first in a series of visions while lying in his bed deathly ill. A messenger from the Creator appeared to him, giving him instructions for the Iroquois people. Handsome Lake recovered and preached these messages to the Senecas in what became known as the Code of Handsome Lake.

After Handsome Lake's death in 1815, his teachings continued to spread and became the foundation for the Longhouse religion. Still a vital force, this religion plays an important role in preserving the Iroquois' sacred and cultural heritage.

Cornplanter (ca. 1740-1836 )

E.C. Biddle, northeastern United States, 1837

Lithograph: Paper, ink, paint L 50.5 x 36.5 W cm; 36026-1.

Cornplanter’s portrait was painted in 1796 by F. Bartoli in New York City. Later this lithograph, based on the oil painting, was published in The History of the Indian Tribes of North America, a multivolume work by McKenney and Hall.

Fragment from Cornplanter’s Cabin

Seneca, collected by Cornplanter's grandson in 1908

Cabin fragment: Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), paper, ink, adhesive, L 23.5 x W 11.7 x H 2.5 cm; 3641-8, gift of G.M. Lehman.

Longhouses

The Iroquois people lived in large bark-covered, barrel-roofed longhouses which extended up to four hundred feet long and twenty-five feet wide. A single longhouse could shelter up to a dozen families through a harsh winter, each with its own private space and a fire shared with others.

Longhouses had either one or two entrances, each adorned with the clan animal of the resident family. Doorways were covered with hide or bark doors. Roofs had covered fire holes that could be opened to provide ventilation and light.

The family sections contained raised platforms covered with reed mats or pelts that served as seats during the day and beds at night. Articles of clothing were hung on the walls or stored in bark bins and baskets along with food and supplies.

In the warmer months, cooking and other domestic activities took place outside the longhouse.

Longhouse Detail, Scale Model of Cornplanter's Grant

Charles F. Rakiecz, Jr., 1997, Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

This model of the settlement of Burnt House at Cornplanter's Grant in 1800 shows the activities during each of the four seasons, carried on by the four hundred Senecas who lived in thirty log cabins scattered near the river. Information, such as the dimensions of structures and number of livestock, comes from the detailed journals kept by the Quakers whom Cornplanter invited to teach the children.