In the 19th century, the Iroquois searched for alternative sources of income. A diminishing land base and the depletion of game and fur-bearing animals left people with very few opportunities for earning a living. Iroquois women recreated their traditional arts of basketry, embroidery, quillwork, and beadwork into new forms for sale to non-Native people. They sold their products at resorts and tourist attractions to the ever-increasing numbers of visitors.

Niagara Falls was the first and foremost American tourist attraction. European and American tourists of all ages, particularly honeymooners, flocked to see the spectacle of the Falls. After the War of 1812, Tuscarora women were granted the exclusive rights to sell their beadwork at Niagara Falls by the American family who owned the land. The Porter family made this offer in gratitude for the Tuscarora's service during the war and for saving the life of a family member.

For well over a century, tourists purchased souvenirs from Iroquois women to take home as gifts and reminders of their personal experiences. They bought whimsical beaded items such as pincushions in the shape of a boot, wall pockets and match safes, model birchbark canoes, and basketry novelties.

The Victorian tastes of the tourists determined what types of items the artists made and how they made them. Many of the novelties were destined for “cozy corners,” which were popular in Victorian homes. Once considered Indian-made curiosities for a Euro-American market, these works are now considered an expression of Native identity and a source of pride. Just try telling Matilda Hill that her “fancies” are tourist curios. The Tuscarora have been able to trade pieces like that bird or that beaded [picture] frame at Niagara since the end of the War of 1812… and she wouldn’t take kindly to anyone slighting her culture.

Richard Hill, Tuscarora/Mohawk, 1982

Moccasins

Iroquois Confederacy, New York or Canada, 1850-1875

Tanned hide, commercial cotton and silk, glass, paper, silver; L 23.0 x W 9.5 x H 7.0 cm; 35068-66 a & b, gift of James B. Richardson, III

Iroquois women continued to make traditional objects, such as these moccasins, to wear on dress occasions. Moccasins were also popular with non-Native clientele, who considered them both exotic and unmistakably "native" and yet could wear them at home as house slippers.

Bag

Iroquois Confederacy, New York or Canada, 1850-1875

Commercial silk and cotton, glass, paper, silver; L 18.5 x W 18.5 cm; 35068-35, gift of James B. Richardson, III, PhD

Iroquois bags and purses in innumerable variations on the same theme sold in the greatest numbers. Their makers incorporated an assortment of materials--beads, rickrack, ribbon--to make the bags eyecatching to both tourists and Native people, who also used them.

New Traditions From Old

Iroquois and other Woodlands artists reinterpreted their established traditions, such as basket-making, beadwork, embroidery, and quillwork, to develop art styles that appealed to the Victorian tastes of American tourists.

Women developed the elaborate fancy basket style that appealed to Victorian tastes, while men prepared the splints and made the utilitarian work baskets. During the winter, families made the baskets, and when summer came, they packed their belongings and moved to resorts to sell their artwork. By the mid-19th century, the arts had become a major economic activity for the Iroquois and their neighboring Northeastern tribes. The women’s earnings played a major role in their families’ survival.

Iroquois women were expert beadworkers, and beaded objects far outnumber the other types of Native items made for sale. The majority were made by Tuscarora and Mohawk women, whose style of beadwork for Victoriana-type items is unmistakable. Large translucent glass beads are clustered together to form ornate, raised floral patterns, usually on dark velvet or red wool.

Generations later, Iroquois women still make Victorian-style beaded “whimsies,” as well as clan medallions and other items, for both Iroquois use and sale to non-Indians.

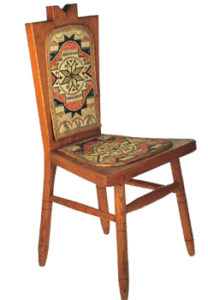

Quilled Chair

Micmac peoples, eastern Canada, 1870-1900

Pine? (Pinus sp.), birch (Betula papyrifera) bark, dye, porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) quills, spruce root?, sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata), glue, sealing wax?; L 41.5 x W 50.0 x H 90.2 cm; 35734-1 a-c, gift of James B. Richardson, III

The seat and back of the chair, which was created by a Micmac artist from Eastern Canada, are totally appliquéd in porcupine quills.

Woodlands Artistry

The Iroquois people were not the only Woodlands nations to make objects for the flourishing tourist trade. Abenaki, Huron, Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot, among others, all participated in this economy.

Some Native groups specialized in particular techniques and crafts. Eastern Canada's Micmac people re-channeled their traditional quillworking skills into producing quilled patterns on birch bark for Victorian customers. The objects they made ranged from small lidded boxes to chair seats and backs totally appliquéd in porcupine quills.

Huron women, adept at working in moose hair and birch bark, taught the Ursuline nuns who arrived in French Canada in the seventeenth century how to work in these materials. When the religious orders established mission schools, the nuns trained the Native women to do fine embroidery in European floral designs. The resulting moose hair objects combined the embroidery traditions of two cultures.

Moose Hair Glasses Case, Spectacles

Huron?, Micmac? peoples , eastern Canada, ca. 1850-1860

Commercial wool, paper, commercial silk, moose hair (Alces alces), dye; L 15.8 x W 4.2 cm; 35460-1

North Eastern United States, early 1800s

Brass, glass, gold?; W 11.0 x H 2.5 cm; 16049-4, gift of Mrs. Davenport Hooker