We go out to the old growth in the forest with the canopy where the bears sleep and the deer sleep to collect the spruce roots. It feels like you get one real big hug from the trees. The people who call us tree huggers, they’re right.

We talk to the trees and we say, “Thank you.” It feels good. That’s why I feel so threatened with all this logging.

Ernestine Hanlon, Tlingit Basketmaker, 1995

Dense evergreen forests rise up immediately behind the narrow strips of beach in southeast Alaska. The forests of the Pacific Coast stand ready to supply many daily needs.

Once, the raw materials from the forest provided the basis for nearly everything that the Tlingit used. Women constructed their baskets from materials harvested from conifer trees—Sitka spruce roots and the inner bark of the western red cedar. They achieved fame for these finely twined baskets decorated with dyed grass applied in a technique termed "false embroidery."

Northwest Coast men are renowned for their tradition of wood carving and painting. They carve everything in wood, from monumental totem poles and canoes, to delicate face masks.

Tlingit peoples, Alaska, collected 1904

Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) root, cedar?; H 22.0 x D 44.0 cm; 3178-123a

Conifers cover over 50 percent of southeast Alaska. Western hemlock and Sitka spruce are the most abundant. The Sitka spruce, Alaska's state tree, grows to 225 feet in height and to 8 feet in diameter, and it can live to be 700 years old. Tlingit women devised a technique for weaving containers and hats from the roots of the Sitka spruce tree. Both women and men wore this type of common work hat, particularly for canoe travel.

Tsimshian peoples, southern Alaska and British Colombia, Canada, collected 1904

Maple? (Acer sp.), mineral paints; L 9.8 x W 16.6 x H 16.2 cm; 3178-33

This type of frontlet is worn as a headdress, usually with a trailer of ermine skins. As a dancer shakes his head from side to side during the dance, white bird down floats out from the crown of sea lion whiskers, missing from the top of this frontlet.

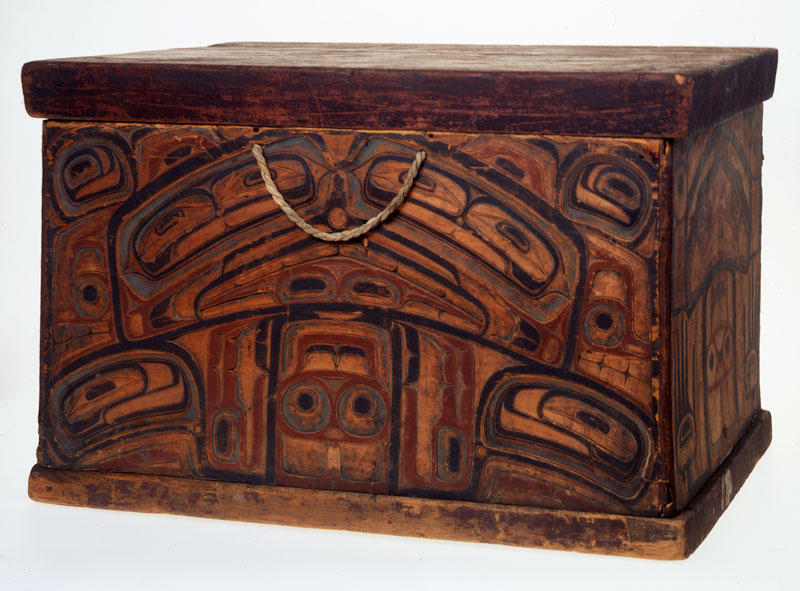

Haida peoples, British Colombia, Canada, mid 1800s

Yellow cedar? (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis), Western red cedar? (Thuja plicata), mineral paints, commercial cotton, iron, steel; L 48.5 x W 75.0 x H 41.5 cm; 3178-109 a & b

Ornately carved chests like this one held the family heirlooms and ceremonial regalia. On special occasions, the house-master sat on a chest; upon his death, it sometimes became his coffin.

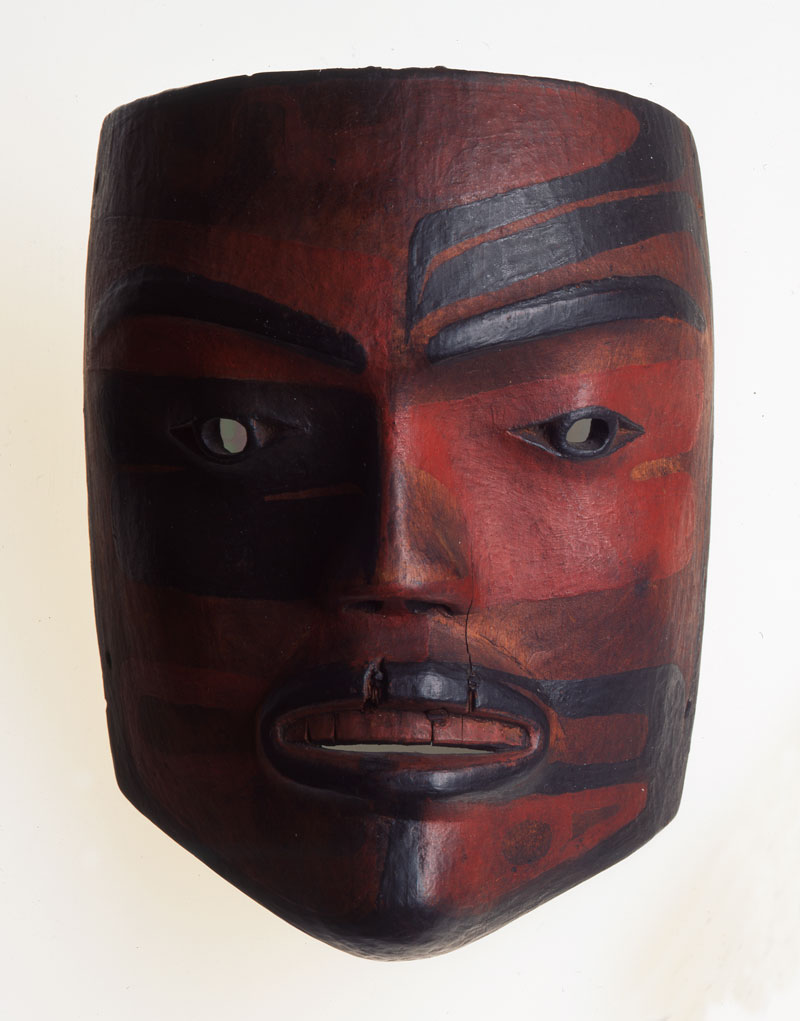

Nuuchahnulth or Kwakwaka'wakw (Kwakiutl) peoples, Kyoquot Sound or Quatsino Sound, early 1800s

Unidentified wood, mineral paints, iron; L 22.0 x W 16.0 x H 8.5; 3178-36

With a crooked knife, a woodworker could carve curved surfaces and the finest details on masks, rattles, boxes, and other decorative items. This dance mask shows the tool marks of a specialist skilled in carving wood.

Gifts From the Forest

Living on the edge of the great evergreen forests, the people were encompassed by a mystic world of spirit beings. They held the cedar in high esteem, for, like the bountiful salmon of the sea, the ubiquitous tree of the forest gave of itself to sustain and enrich their lives.

The climate of the Northwest Coast is temperate and damp. Currents warm the ocean, which tempers the prevailing winds. The warmed air is trapped by the high peaks of the coastal mountains, preventing cold, continental air from dominating the climate. The mountain barrier also blocks the vapor-laden breezes, creating abundant rainfall, as much as 100 or more inches a year, and a lush evergreen forest.

The effect of this excessive precipitation is apparent in the luxuriant vegetation that covers the mountains. Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), Western red cedar (Thuja plicata), and yellow cedar (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis) are the dominant trees. Black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa), the willow (Salix sp.), and the red alder (Alnus rubrum) and the Oregon alder (Alnus oregona) are found along the streams and river bottoms, along with Douglas maple (Acer glabrum,), shore pine (Pinus contorta), and crab apple (Pyrus fusca).

Hemlock is the most abundant of the woods, but because of its weight and coarse grain, it was of least value to the Tlingit. Spruce is second in quantity, but was economically the most important wood in the life of the people. Houses were built with it; canoes were constructed from its trunk; the roots were used to make baskets, rope, and fishing gear; and the inner bark was eaten.

The cedars were the most valuable trees, but were found only sporadically. The red cedar, from which the large traveling and war canoes were made, grows only in the southern regions of the northwest coast. The yellow cedar is more common in Alaska. Both are fine-grained and were used for carving and household decoration: for chests, boxes, and other domestic purposes. Mats, baskets, rope and clothing were made from the inner bark.

Many different kinds of berries are native to the Pacific Northwest Coast and are found in great abundance. Blueberries (Vaccinium uliginosum), huckleberries (Vaccinium parvifolium), salmonberries (Rubus spectabilis), cranberries (Vaccinium oxycoccos), strawberries (Fragaria sp.), and raspberries (Rubus sp.) were important to the Tlingit. All of these were eaten fresh, and most of them were also preserved for winter use.

From the rainforest came a wealth of raw materials vital to the way of life, art, and culture of the Tlingit. They recognized these as gifts of nature and accepted them with gratitude.

Tlingit Canoes

The canoe and more recently the motorboat are the primary means of travel for the people of the Northwest Coast. Access to everything—other villages as well as fishing and hunting grounds—is by water.

Canoes were normally built in the winter, when the Tlingits were not as occupied with subsistence activities. They were constructed from the straight-grained wood of red cedar trees that had been blown over by the wind or felled by building a fire at the base. The log was hollowed out with hand tools and shaped by filling the cavity with water and dropping hot stones into it. Pieces of wood were then wedged across the gunwales to give the sides the desired degree of flare. The outer sides of the canoe were often painted and the bow carved.

The Tlingits made different types of canoes that varied in size and shape depending on their function. Small canoes carried two or three persons, whereas larger ones could hold 60 people and be 40 feet long.